A guest post by Mary Lyn Maiscott, published for the third anniversary of the mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas

"Welcome to Uvalde." I noticed the sign as my husband and I approached the small city in our grey rental Prius. U-vaul-dee. Three little unified syllables—until recently unknown to most the world, myself included—now heavy with loss, pain, and death. It felt as though Bob and I had driven, taking Highway 90 from San Antonio, into a tragedy.

I pulled into the Motel 6 on East Main Street, where a "Fox News—Austin" van sat in the parking lot. This was the only place I could find that hadn't been fully booked by media people in town to cover the one-year anniversary of the massacre at Robb Elementary School on May 24, 2022. That day an 18-year-old killed 19 fourth-graders and two teachers with a military-style weapon as police—stunningly, inexplicably—waited in the hallway.

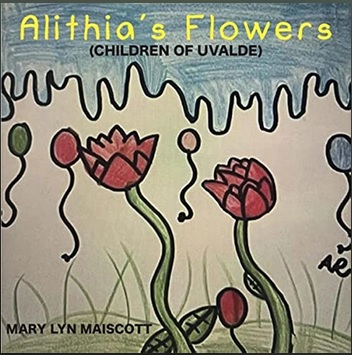

The song's cover art features a drawing by Alithia Ramirez.

I had traveled from New York City to Uvalde, Texas—beloved home state of my mother, where I'd last set foot long ago, as a teenager—not to write a story but to sing a song, "Alithia's Flowers (Children of Uvalde)," inspired by a drawing created by 10-year-old Alithia Ramirez, one of the victims at the school. In it, red tulips with undulating stems reach with a kind of giddy joy toward a dripping sky with a message only enhanced by its endearing errors: "Happniss come's first!" (Nevertheless, because of what happened to Alithia, it always feels to me as though that sky is weeping.) I'd been invited to perform my song for a commemorative event that was subsequently canceled. But here I was in Uvalde anyway, to meet Alithia's family and sing the song for them—we would meet up at the town square on the anniversary, the next day.

Shortly after recording "Alithia's Flowers," about a week after the shooting, I'd contacted Alithia's parents, Jessica Hernandez and Ryan Ramirez, through social media. In my first message exchange with Jess, she told me about Alithia's dreams of studying art and her just-discovered TikTok page (under the handle "evilartist"). Every time Jess responded to me, her profile picture, a thumbnail photo of Alithia in a rainbow-colored tee augmented with angel wings, popped up. I was glad Jess couldn't see me because it became impossible to hold back tears.

In the correspondence that followed, Jess would often write, in her understated way, "It's just hard for me." I took that to mean she felt blown apart psychically. The immensity of her pain was difficult to grasp. Once, at a total loss for an appropriate response, I asked if she might want me to send some NYC bagels (she did). And I hoped the recording of "Alithia's Flowers" had brought her and Ryan comfort, however slight—Ryan told a podcaster that he "just couldn't believe it" when they found out, on New Year's Eve 2022, that DJ Michael J. Mand had named it song of the year on OWWR, a Long Island radio station.

After our arrival in Uvalde, Bob and I set out to explore the city, one with deep Mexican roots, located on the southern edge of Texas Hill Country. Our motel was only about a mile from downtown, so we walked there along the highway, traffic thrumming past us. We stopped at a Walgreens to get toothpaste, and right inside was a shrine of sorts: a table with 21 cards, each illustrated with steps leading to a shining cross and the name of one of the victims. Soon we would see this kind of tribute repeated in store windows—21 candles at Vapor Way, 21 rainbows at Doll Haus Boutique, a cross at Southwest Uniforms with all the names (Xavier, Maranda, Nevaeh, Jayce…).

But the most impressive tribute was still to come, because to take a walk around downtown Uvalde, with its weathered buildings evoking the film The Last Picture Show, is to be under the gaze of children frozen in time. Gigantic murals of the victims adorn the exteriors of various structures. When we stopped to eat at a luncheonette that retains its vintage Rexall Drugs sign, I could see through the glass sweet-faced Makenna Elrod, surrounded by her animals, depicted on the side of a gift shop across North Getty Street. Around the corner, on what's now called Alithia's Art Alley, we found Alithia's portrait: above us beamed the shy smile that had become so familiar to me through the photos and videos of Jess's posts (which also showed a spirited girl into her dance moves).

Reminiscent of outsider art, the memorials had sprung up shortly after the horrific event and now surrounded a shallow pool with a three-tiered fountain.

In the town square, a green with feathery-leaved pecan trees, we discovered Alithia's handmade memorial, along with those of all the other "angels" (as they're sometimes called). Reminiscent of outsider art, the memorials had sprung up shortly after the horrific event and now surrounded a shallow pool with a three-tiered fountain. Most of them overflowed not only with flowers but with such items as stuffed animals, silver star balloons, action heroes, teddy bears, pinwheels—in one case a purple wooden cabinet had been transported, probably from a child's bedroom, to hold toys, photos, and a sign that said, "You are meant for big things."

On the anniversary the next day, after bells rang at 12:39 p.m.—to mark the beginning of the rescue at the school—Bob and I returned to the square. Amid the mourners visiting the memorials, the media with their camera setups, and a few police officers, mariachis, resplendent in their black, silver-trimmed uniforms, filled the square with their passionate music.

I was chatting with an amiable Billy Graham chaplain when I spotted Jess, Ryan, and their children Akeelah, then six, and Jonah, then four, moving toward me as a unit, a vision in purple. They were showered in Alithia—wearing her favorite color, pins with her image, Jess's necklace with a tiny black-and-white photo of her and Alithia's faces and another with Alithia's fingerprint. As I hugged Jess, she felt insubstantial, a small body holding so much devastation, her freckled face giving none of it away. When I crouched down to say hello to Akeelah, she sweetly pressed her cheek against mine. Ryan, who has his older daughter's name tattooed on his forearm, told me that they had just been to Alithia's "resting place" (Hillcrest Memorial Cemetery, Crepe Myrtle Section).

I performed the song for the family and some passersby there in the square. The roaring trucks on the nearby highways nearly drowned me out, but when I glanced up from my guitar, I could see the rapt faces of Jess and Ryan. The Graham chaplain and his wife, also a chaplain, then asked the couple if they wanted to pray, and they all, children too, formed a circle under a tree, praying with their heads down.

Often on social media, Jess had revealed her distress ("I miss my baby girl!"), but today—of all days—she was very composed. She began to tell Bob and me about an amphibian Alithia had liked, the axolotl, which I'd never heard of. "It's cute!" Akeelah chimed in. Later I would read that the axolotl remains larval rather than metamorphosing into an adult form, and this made me think of a hashtag Jess sometimes uses when she writes (as she always writes) about Alithia: #forever10.

The family left to go to a city-sponsored prayer service at the Civic Center but said they'd see us later at the public candlelight vigil near the center. (As it turned out, they left the vigil early and we wouldn't see them again; they'd moved about an hour away from Uvalde.)

At the vigil Bob and I sat at the top of a small hill, surrounded by people in T-shirts with images of the children they had lost, or angel wings framing the term "the 21," or just the words "Uvalde Strong." On the stage of the amphitheater below us, a preacher, a young woman, intoned: "Father God, you are the mender of broken hearts and there are so many broken hearts here tonight." Later an announcer called for people to "take out your boxes" and release the butterflies inside, but when the boy next to us unfolded his, a monarch practically stumbled out of it and stayed in the grass; others did the same, and Bob worried they would all be crushed when we left. Everywhere we looked we saw sadness, but when the evening darkened, someone came along with candles. People lit each other's in turn with their own candle flame until the night was studded with uncountable tiny lights, like little stars that had found their way to us.

There are invisible waves of grief in this town; they can suddenly break in your direction.

I did my song in the square one more time, the next night. We walked the few blocks there from the historic Benson Guest House, where we were now staying, to make a video, figuring the traffic would be quieter. Near the fountain I noticed a grizzled-looking man in a denim shirt, staring off toward the street. I went up to him and explained about the video, saying I hoped we wouldn't disturb him. He told me he was the grandfather of one of the victims. There are invisible waves of grief in this town; they can suddenly break in your direction. I asked him the name of the child. Layla, he answered. I knew the name but didn't remember anything specific. He graciously added, "Thank you for your kindness in remembering the children."

The next morning I took my coffee out onto the guest house patio and sat down at the wooden table, honeysuckle vines gently waving above me on the latticed canopy. Then I noticed the mural on a building across the alley: "Layla Salazar" was written in big loopy letters. I looked at the image of her jumping hurdles and remembered: the petite girl who could run like the wind. "Sweet child o' mine," the mural proclaimed. Later I would learn that she'd traced her name, along with a heart, in the dust on her grandfather's truck and that it was still visible a year later.

Layla had been Alithia's classmate at Robb Elementary, located in a leafy neighborhood within walking distance of downtown. To get there, Bob and I took Geraldine Street to Old Carrizo Road. On the way, an older man putting out his trash asked if we were going to the school. When we said yes, he responded in an ominous tone, "Be careful." This was puzzling—maybe he thought we were with the media, who were not totally welcome. We'd seen "No media past this point" signs around town.

The school reminded me of my own grade school in rural Missouri—long, low-slung, many-windowed. Not long ago a place of mayhem and chaos, it was empty and quiet now, slated for destruction; a ghost school that had housed children, in all their messiness and sweetness, had even kept them safe—once. It was now surrounded by a fence that was partially draped in a funereal black cloth. On the fence hung a couple of signs that had taken on a cruel irony: "All visitors must get pass at office," with a bouquet of flowers pressed against it through the chain link, and "Open carry prohibited," with a gun graphic slashed with a red line.

And again we saw the 21 names—on crosses adorned with rosary beads; paper bags holding battery-powered candles; a sign that included Franklin Roosevelt's famous WWII line, "A date that will live in infamy." For the "hero teachers" Eva Mireles and Irma Garcia, who were killed while trying to protect their students, metal apples popping up from the ground conveyed messages like "Thank you for caring." (Garcia's husband died of a heart attack two days after her murder.)

Undoubtedly along with the other people who'd gathered nearby, I stared at the school and thought of all that had transpired here, all we'd heard on the news: the teenager with his AR-15 (having first driven into a nearby ditch), the frantic parents, the hesitant police, the children inside hiding as best they could and calling 911. Across the street, startlingly, was a funeral parlor, Hillcrest Memorial; I soon learned that some of the kids escaped when the shooting began and ran there for refuge.

Adam Martinez's son Zayon had been in second grade at Robb, but in a wing away from the shooting—he now had trouble sleeping and was being home-schooled. Adam, the founder of Keep All Righteous Minds Aware (KARMA), a Uvalde activist group focusing on school safety, invited me to sing "Alithia's Flowers" for a video for the group's social media. In the game room of his home, I performed the song with Adam joining me on second guitar. (Like many other polite denizens of Texas, he called me "ma'am.") His wife, Raquel, made a video recording from across the pool table as their 12-year-old daughter, Analiya, holding their baby, Amora, watched.

While talking with him afterward, I discovered I'd read about Adam, identified only as a Robb father, in The New York Times just a few days before. He was accused of disrupting a local school-district meeting when he quietly but persistently asked the police chief, standing against a wall, about a new police hire (he showed me a video someone had taken of this); he'd subsequently been banned from all Uvalde school property for two years. This was rescinded after Adam, with the help of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), threatened a lawsuit.

All of this, taking place so close to the memorials, seemed incongruous, but it was just life going on after death.

Our last night in Uvalde, a Friday, as Bob and I walked back from Vasquez, a Tex-Mex restaurant a distance from downtown, we suddenly found ourselves at the square, where the "Party in the Plaza," as a banner announced, was going full-blast, hosted by a radio station playing "Don't Stop Believin'" from a tent-like booth. Kids hopped along in a potato-sack race, and vendors sold eye-catching trinkets. All of this, taking place so close to the memorials, seemed incongruous, but it was just life going on after death.

After a while, Bob went back to the guest house, but I wasn't ready. I sat down on a bench—decorated with a long, winding, diaphanous white ribbon—near the fountain. I looked at the shimmering pool, the highway headlights, the streetlamps, a twinkling memorial cross. The moon was gauzy, as though covered with that same diaphanous ribbon. It is strange, I thought, the Uvalde experience: sometimes I feel I could cry enough tears to feed this fountain (and still would not match the tears of this town), but at other times I feel expansive, as though I've tapped into something that goes beyond all this, even all the suffering—something that perhaps Alithia tapped into with her swaying tulips, her invocation of happiness. I decided to walk around the fountain pool to take in the memorials again and perhaps see Layla's grandfather.

I stood in front of Alithia's memorial, topped with a "Be kind" sign, one last time. Then I took out my notebook and wrote a message to her, thanking Alithia for touching my life with her exuberant flowers, which sprouted from the cracked dry soil of Uvalde.